Understanding biofilms in food production

November 15, 2022

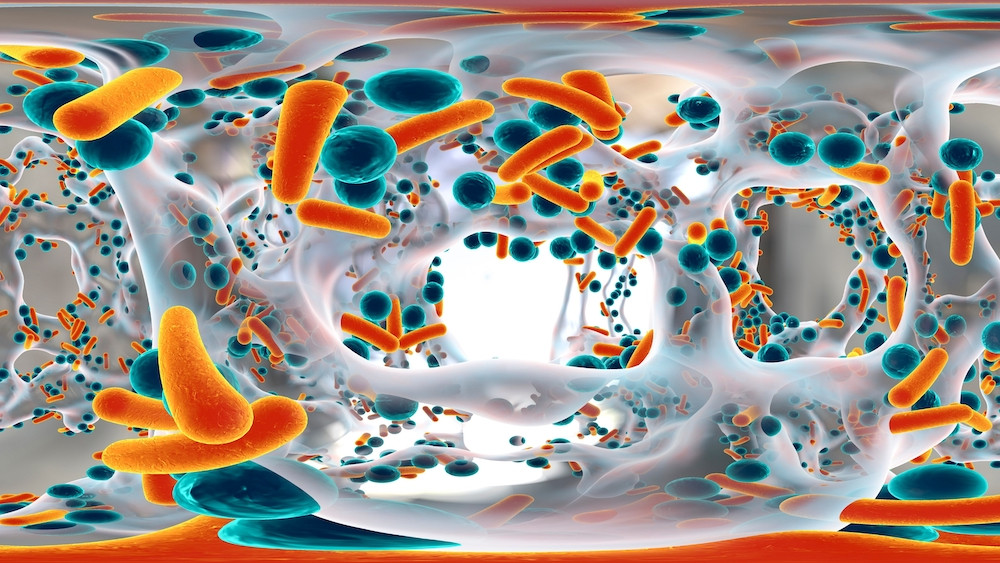

Biofilms are an invisible threat to the food industry. With these aggregates of microorganisms thriving on food processing lines, they pose a formidable challenge for food manufacturing, safety, and quality control. Not only are these microorganisms responsible for food spoilage, they also have the ability to cause premature wear and tear on manufacturing equipment.

“Biofilms are colonies of microorganisms—including some of the most common foodborne pathogens—that form on a surface,” writes Decon7 (D7) in their piece on ‘What Is Biofilm and Why Is It Dangerous? Everything You Need to Know.’ “Unlike free-floating bacteria that are relatively easy to remove with disinfectants, biofilms form a protective layer of extracellular polymeric substances that make them more challenging to remove.”

Leaving biofilms unchecked in your facility can disrupt major aspects of food production; from ruining manufacturing schedules to delays in product delivery. In worse cases, it could breed foodborne illnesses in your facility. This is why taking a proactive approach is key to biofilm prevention.

How can we prevent biofilms in food plants? Improve your facility’s prevention protocols by understanding the causes of recurring biofilm formation and disinfectant resistance.

Defining biofilm and tracing its formation

Biofilm is a cluster of microorganisms that contains an extracellular polymeric substance matrix, which causes cells to stick to one another or stick to a surface. Modern food processing lines are a suitable environment for these microorganisms to form. This is due to the food manufacturing plants’ tendency to perform mass productions, conduct long and complex production periods, and contain spaces with large biofilm growth areas.

Apart from a plant’s hygiene, the D7 team enumerates the five steps biofilm can build up inside a facility:

- The reversible attachment to a surface—this is when intervention is key.

- The formation of a single layer and production of a protective matrix.

- The formation of a microcolony with multiple layers.

- The maturation and growth of the biofilm within the protective matrix.

- The proliferation of pathogens dispersed from the biofilm to form new microcolonies and repeat the process.

In the academic dissertation by Luanne Hall-Stoodley, J. William Costerton, and Paul Stoodley called “Bacterial biofilms: from the Natural environment to infectious diseases,” they discuss the challenges biofilm growth poses to players in the food industry. “They allow bacteria to bind to a range of surfaces, including rubber, polypropylene, plastic, glass, stainless steel, and even food products, within just a few minutes, which is followed by mature biofilms developing within a few days (or even hours).”

Biofilm’s attachment properties highly contribute to its formation. Hydrophobicity, electrostatic charging, interface roughness, and topography are elements to watch for biofilm growth. Of course, a manufacturing plant’s hygiene protocols is another factor.

Relevant biofilms in the food industry

Conrado Carrascosa et al’s study on “Microbial Biofilms in the Food Industry” broke down the most relevant biofilm strains in the food industry. They emphasized how the processing environments in manufacturing plants can act as artificial substrates for bacterial growth. Structure materials such as wood, glass, stainless steel, polyethylene, rubber, polypropylene, and many more can contribute to these mixed microbial communities.

Here are some samples of biofilm-forming pathogens that food manufacturers should be aware of:

Pathogens: Bacillus cereus

Characteristics: Gram-positive, spore-forming, facultative

Contaminated Food: dairy products, rice, vegetables, meat

Example of Spoilage Effects: abdominal pain, watery diarrhea and vomiting symptoms

Pathogens: Campylobacter jejuni

Characteristics: Gram-negative, aerobic and anaerobic

Contaminated Food: animals, poultry, unpasteurised milk

Example of Spoilage Effects: bloody diarrhea, fever, stomach cramp, nausea and vomiting

Pathogens: Escherichia coli

Characteristics: Gram-negative, rod-shaped, facultative anaerobic

Contaminated Food: raw milk, undercooked meat, fruits and vegetables

Example of Spoilage Effects: severe stomach cramps, diarrhea, and vomiting

Pathogens: Listeria monocytogenes

Characteristics: Gram-positive, rod-shaped, facultative anaerobic

Contaminated Food: dairy products, meat, ready-to-eat products, fruit, soft cheeses, ice cream, unpasteurized milk, candied apples, frozen vegetables, poultry

Example of Spoilage Effects: Listeriosis in the elderly, pregnant women and immune-compromised patients which can develop severe infections of the blood stream (causing sepsis) or brain (causing meningitis or encephalitis)

Pathogens: Salmonella Enterica

Characteristics: Gram-negative, rod-shaped, flagellate, facultative aerobic

Contaminated Food: Poultry meat, eggs, unpasteurized milk, undercooked meat

Example of Spoilage Effects: can cause gastroenteritis or septicaemia

Once they form, they pose a major threat as they cause foodborne illnesses and economic loss. Dairy manufacturing plants serve as a perfect example for the effects of biofilm in a brand. In dairy plants, processes and structures such as pipelines, centrifuges, cheese tanks, and packing tools can act as surface substrates for biofilm formation at different temperatures.

The structures mentioned above can encourage the increase of colonizing species. This is why it’s of great importance that accurate methods to address and prevent biofilms in situ should be in place to avoid contamination and ensure quality in manufacturing.

Preventing biofilms in the manufacturing line

People experience difficulties in identifying and eliminating biofilms. It can cause contamination even before you sense a problem during the manufacturing process. It is capable of growing on various surfaces, especially with distinct biotic and abiotic compositions. Leaving biofilms untreated can impact the bottom line of your facility’s process.

It is difficult to treat due to its extracellular matrix. This is the main reason why there are plenty of disinfectant products that have difficulty penetrating the biofilm’s barrier. What decreases its opportunity to grow would be an updated hygiene program and constant sanitation. However, this wouldn’t be enough for invisible biofilms present on difficult-to-reach surfaces.

This is why daily sanitation and periodic deep cleans should be a top priority for food manufacturing plants. “In order to prevent microorganisms entering food production, factories, and the employed hygienic equipment should be designed to limit microorganisms from accessing,” writes Carrascosa et al. “Aseptic equipment must be isolated from microorganisms and foreign particulates. To prevent microorganism growth, equipment should be designed to prevent any areas where microorganisms can harbor and grow, along with gaps, crevices, and dead areas.”

Disinfectants such as alkyl amines, chlorine dioxide, and quaternary ammonium blends are staples in disinfectant programs. With certain food manufacturers, they opt to have a go-to disinfectant that deals with biofilm prevention. In J.S. Palmer’s study on “The role of surface charge and hydrophobicity in the attachment of Anoxybacillus flavithermus isolated from milk powder,” they discussed how certain disinfectants have perfected biofilm elimination in the past few years.

“To date, many efforts have been made to reduce biofilm formation on food industry surfaces, but those works were based mainly on new disinfectants with different efficacies,” writes Palmer in their study.

“Nowadays, disinfectants are the best ally to eliminate biofilms. However, other research fields, such as the composition of surfaces for materials to prevent bacterial adhesion and developing phages to combat biofilm-forming bacteria, have obtained favorable results.”

One great example on how biofilm disinfectants evolved, despite biofilms' tendency to build immunity towards certain disinfectants, is the Decon 7 sanitizer and disinfectant. It efficiently eradicates biofilms from surfaces with no mechanical action needed. With this formula, it disrupts the protective matrix with detergents and eliminates bacteria at the DNA level.

“By using D7 for daily sanitation and deep cleans, you can not only reduce the risk of biofilm formation, but also save time and money,” writes the D7 team. “Biofilms can also cause premature wear and failure of equipment, so in addition to addressing safety concerns, proper treatment and removal can maintain the longevity of equipment.”

Carrascosa’s study highlighted that “the ability of bacteria to form biofilms is greater than the discoveries.” The best solution to keep manufacturing lines safe from biofilm is to understand how biofilms are evolving and investing on constant deep cleans. Staying ready and educated will do wonders on futureproofing your manufacturing plant’s safety.

References:

- Team, D. (2022, February 1). What is biofilm and why is it dangerous? everything you need to know. The Power of D7 Foam Blog. Retrieved July 19, 2022, from https://blog.decon7.com/blog/what-is-biofilm-and-why-is-it-dangerous-everything-you-need-to-know

- Team, D. (2022, March 22). Preventing antibiotic resistant and recurring biofilms. The Power of D7 Foam Blog. Retrieved July 19, 2022, from https://blog.decon7.com/blog/preventing-antibiotic-resistant-and-recurring-biofilms

- Carrascosa, C., Raheem, D., Ramos, F., Saraiva, A., & Raposo, A. (2021, February 19). Microbial biofilms in the food industry-A comprehensive review. International journal of environmental research and public health. Retrieved July 19, 2022, from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7922197/

- Hall-Stoodley L.J., Costerton W., Stoodley P. Bacterial biofilms: From the natural environment to infectious diseases. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2004;2:95–108. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro821.

- Palmer J.S., Flint S.H., Schmid J., Brooks J.D. The Role of Surface Charge and Hydrophobicity in the Attachment of Anoxybacillus Flavithermus Isolated from Milk Powder. J. Ind. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2010;37:1111–1119. doi: 10.1007/s10295-010-0758-x.

Other Articles: